Podcasts are still quite popular and new ones appear everyday. It is a fantastic format and I encourage everyone to give it a try.

This of course involves the process of recording audio and if you haven’t done that before, there are a few things to keep in mind to get the best possible result, no matter what your budget is.

In this blog post I want to talk about the most important things for achieving a great sounding recording for your podcast. The principles discussed are not limited to podcasts though and apply to other audio recording situations as well.

There are some sections which go into an extra bit of technical detail. If it is too much for you, feel free to glance over them and come back later if you care to learn more.

The Source

It doesn’t matter what you record, whether it is speech or music or ambient sounds, most problems can and should be fixed at the source. Here you have the biggest leverage on how good your recording will sound like and how much post-processing will be needed.

The Room You Record In

Rooms do have a sound on their own. You’ve been in big halls with a lot of reverberation, or in tiny little rooms which sounded dampened and lifeless. Ideally you want a room that does not have a lot of reverb, just enough so it doesn’t sound completely dead.

When you think about where to record, a bad choice would be a kitchen, a bathroom or big, empty rooms with hard surfaces like tiled floors because they tend to have a lot of reverb and undesirable echos.

You can easily test your room by standing in the middle of your desired recording room clapping your hands or snapping your fingers. Listen carefully after each loud clap how much reverb / echo of your clap you can hear. How long is the high frequency trail of that clap echo? Then try different rooms and choose the room with the least echo and reverb.

Of course you can also go ahead and reduce the room reverb by putting up acoustic panels on the wall. The typical square foam panels will help with reducing the reverb. Also consider putting a carpet into the room if it has not one already. Lastly you can try to put improvised dampening around you while recording. I sometimes put up mic stands in a T shape, put blankets over it and surround myself with those with a bit of distance. Acoustic treatment for rooms is a hole different problem domain though but there are great beginner guides for the basics out there.

Room Noise

Another thing to be mindful of is the noise that surrounds you. Be it the street next to your house and its traffic noise, an AC or fan, squeaking chairs or floors or the washing machine next door. All of this could be picked up by a microphone and will degrade your signal. If you want to get rid of this noise when editing you’d use something like a gate to mute the signal when nobody is speaking and open it once someone is speaking. But when you have a lot of background noise, this noise is muted and unmuted as well and it creates a messy listening experience.

So when choosing a room, keep the noise in mind and if you can, pick the quietest room with the least amount of reverb. It will always be a compromise unless you’re in a sound studio so experiment and try what works best in your situation.

The Microphone

The microphone is quite essential in the recording process of course, but even the greatest microphone will not yield great results in a bad sounding room. That is why the microphone is addressed after the room.

There are a few different types of microphone and almost all of them are suitable for recording voices for a podcast. The most commonly used mics for vocals are dynamic and condenser mics. Both of these come in variants with small or large membranes or diaphragms. Both types are available either as headset or as standalone microphone.

Condenser Microphones

Large diaphragm condenser mics are very common for recording vocals in a music studio. They capture the full frequency spectrum of the voice without too much coloration. But because they are supposed to pick up all the nuances, they will also pick up any noise in your room as well as the reverb.

In a situation where your room is not ideal, I’d recommend using a headset with a small condenser mic which will be closer to your mouth and more directional which means it won’t pick up as much of the room ambience and noise. A pro-level headset example would be the beyerdynamic DT-297 but there are cheaper alternatives.

Headsets also have the advantage that you don’t have to sit still in front of a mic stand. A mic stand plus a big condensor or dynamic mic also block the vision to some degree. If all the participants sit in the same room for recording, a headset allows you to move your head freely and doesn’t obscure your eye contact with the other participants. You can sit however relaxed you want. Something you can’t do with a mic on a stand.

No matter if you’re using a large diaphragm condenser mic or a small one in a headset, both types will need phantom power. Usually every pre-amp you can plug your mic into should have a switch to enable phantom power – even standalone recorders like the ones from Zoom or Tascam.

A benefit of this is that condenser mics usually have a higher output level than dynamic mics which means you can get away with getting a cheaper audio interface or mixer – but more on that later.

Dynamic Microphones

Dynamic microphones are widely used in live situations and on loud instrument sources. On almost every stage on this planet, vocal performers will use a dynamic mic and their instruments, especially drums and guitar amps, will be miced up with dynamic microphones as well. The reason for this is that they are constructed in a much simpler way. Basically they work just like a speaker in reverse.

Their simpler construction makes them more forgiving when it comes to physical stress – as in dropping the mic, humidity or extreme sound pressure levels. They also don’t require phantom power which adds to their versatility.

The slight drawback of dynamic mics is that they usually have a more pronounced sonic character than the condenser mics. Dynamic mics for live situations for example, will almost always boost the mids and high mids to give vocalists more presence in a live mix. In a studio, especially with singers who have a high and/or thin voice, such a mic will not work well.

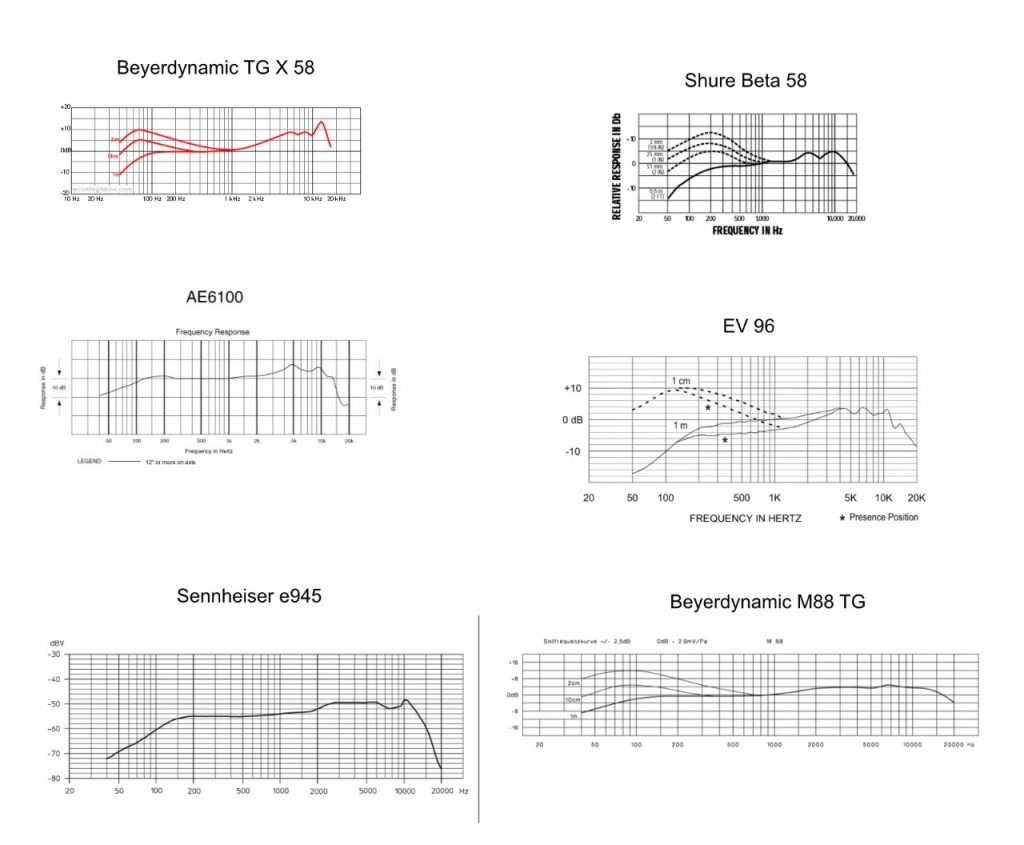

(This is an overview of the frequency response of common dynamic mics for live situations. All of them will boost the mids starting from 2kHz)

A great dynamic mic for vocals is the Shure SM 7B as its frequency response is fairly even which makes it sound very round and full. Its one of the most popular dynamic vocal mics in studios. Its major drawback is that its output level is quite low which requires a beefy pre-amp to operate it properly.

Summary

For podcasting the simplest, most convenient and adequate option would be a headset with a condenser mic. Phantom power is available in a wide variety of recording systems, it’s comfortable, the mic position is consistent throughout a recording and it does not require a powerful pre-amp.

You also don’t need mic stands and you are free to move around to some extent during the recording.

Because I don’t own headsets but quite a collection of studio mics, I often record podcasts with large diaphragm condensers or the Shure SM 7b. I prefer it sonically but it comes with all the drawbacks of practicality and convenience.

Another alternative are lapel mics, which are even more convenient to wear but the ones that sound decent cost a lot of money and are a hassle to connect to a pre-amp.

The Audio Interface

Now that we talked about the room, noise and the microphones it is time to talk about the device which will capture the audio and convert it to digital.

If you are recording a podcast with multiple participants, make sure that your recording device has sufficient inputs so that you can record each participant to a separate track.

The Pre-Amp

No matter what recording device you choose, it will all have a pre-amp unless you are using a USB mic, which will have the pre-amp built in.

Because the output levels of most microphones are quite low, they need to be amplified to line level so that they can be played back through regular hifi/monitor systems (which further amplify the line level signal to speaker level).

If the output of a microphone is quite high (some get close to line level), less amplification is needed.

If the output of a microphone is low (as the Shure SM 7B), more amplification is needed.

The noteworthy thing about this simple equation is that existing noise in the signal or in the circuitry of the interface or the microphone will be amplified as well.

This becomes even more relevant if you bought a very affordable interface with a weak pre-amp and pair it with a very low output microphone. As you dial up the gain on the pre-amp, more and more background noise will become audible in the resulting signal. On a cheap interface I have to dial up the gain to maximum to have a usable level from my SM 7b and the noise as well as pre-amp distortion are very present at this point.

This applies basically to all pre-amps like in portable recorders, audio interfaces, dedicated pre-amps, mixers and mixing consoles. Usually the most affordable product line of any of those categories of any of the vendors will have weaker pre-amps than the next higher level product line of the same vendor.

I’d recommend getting something with pre-amps that have at least 50 dB on tap – ideally 60+ dB. With that amount of gain available, you should never need to turn it up more than 2/3, even on quieter sources or with low output microphones. In my experience, most pre-amps stay reasonable quiet up to this point.

A lot of cheap pre-amps will only go up to 35 dB and for an SM 7b recording normal conversations, this is not enough. You’d have to crank up the gain knob and as a result will get noise and distortion. An interface with twice the gain will leave you a lot of headroom before the pre-amplifier starts to distort and before its own electrical / thermal noise becomes audible.

However, if you are going for phantom powered condenser headsets, you can get away with weaker / more affordable pre-amps.

Focusrite and Zoom are two brands with quite affordable recording products which work great. Focusrite’s most affordable interfaces have quite useful and impressive pre-amps with lots of headroom and very little noise. The Zoom recorders, especially their L-12 podcasting machine is offering a lot of flexibility for your recording needs. Most notably for podcasts, it has 5 dedicated headphone jacks which you can mix individually. When you record with headsets this saves you an extra headphone amp (which would amplify the line level to headphone level).

In general though, just check the reviews and specs, compare them and look up things you don’t understand. Check that the manufacturer keeps the drivers up to date for your platform and that a broad group of people is generally happy with the product in customer reviews. Read especially the one and two star rating reviews if there are any.

Nothing Else?

Of course there are more aspects of a audio interface that impact the quality of the recording but they are less relevant if you have optimized everything discussed up to this point.

Especially for recording conversations, the quality of the Analog-To-Digital and Digital-To-Analog conversion for example are neglectable.

Hardware Effects (Compressors / Expanders / Gates)

In professional studios, usually more hardware components come after the pre-amp in the signal chain before the signal is sent to an audio interface to convert it to digital. These are usually effect processors which either control the dynamics (change of loudness) in a signal or to minimize noise.

However I don’t think these are necessary for recording podcasts if you get your environment and recording settings right, especially when you’re starting out. Chances are that you make your signal worse than better if you don’t know exactly what you’re doing.

Recording Settings

After all the hardware lets talk about how you should set the recording up. In general, record each participant to a separate track on your recorder or in your software.

Gain / Levels

One of the most important things when recording is to set up the recording level / loudness correctly. Before you start recording, always do a soundcheck where you talk normally but also laugh out loud for example. Try to explore your natural dynamic range when you talk to people. Its quite common that people will talk rather calmly most of the time but when something funny comes up, they will laugh quite loud.

While you are doing this for yourself and the other participants, check the recording levels on your recorder or software on the computer.

What you want to avoid is that the signal “clips” at 0 dB. When a signal is louder than that, the sine wave will be clipped at 0 dB and that will result in very nasty sounding digital distortion. When it goes louder than 0 dB, usually this is signalled with a red LED or red warning indicator in your DAW (Digital Audio Workstation aka your audio editor).

The level ideally should be between -12 and -18 dB when talking normally. The louder voice or laughter should ideally stay below 0 dB.

It is not a problem if the signal is clipping for a split second in the loudest segments of the recording. Just make sure that 98% of the recording is in the -12 / -18 dB range.

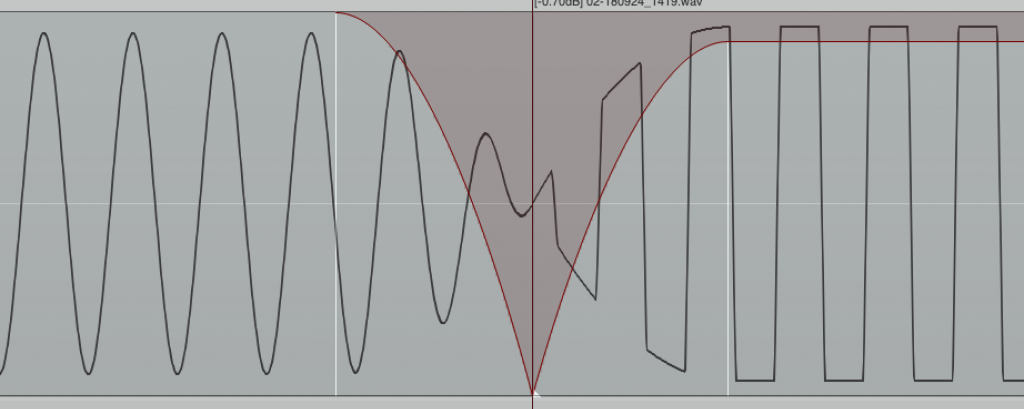

To demonstrate what happens if a signal is clipping, I have generated a 220hz sine wave, which I then amplified to +12dB. Left you see the perfect sine wave, right the amplified and clipped sine wave.

Both sine waves played after another sounds like this:

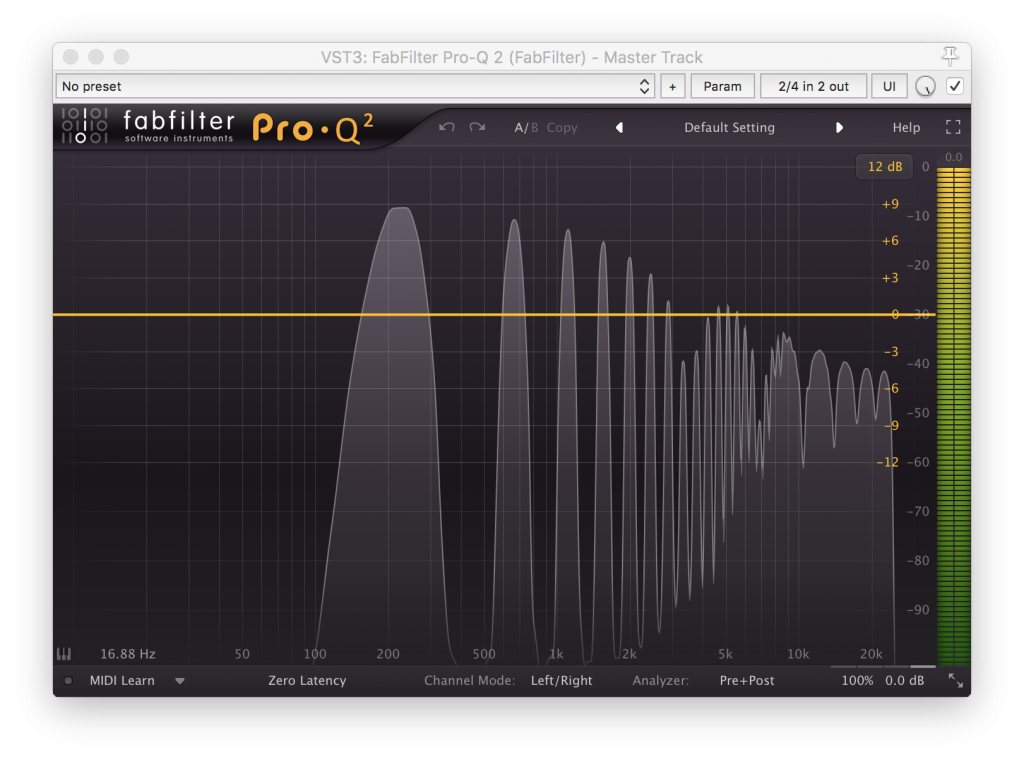

When looking at the two through a spectrum analyzer (in this case a graphical EQ), you can see the difference between the clean 220hz sine wave

and the clipped one which now has a lot of extra harmonics / distortion:

Record in 24Bit/48kHz

Next lets talk about the sample rate / frequency. Depending on your audio interface, the default it will be set to may either be 44.1 or 48kHz. 44.1kHz is the CD standard but since that is an obsolete medium I go with 48kHz which is also the standard for video productions. Quality wise it really doesn’t matter. Just make sure its not less than 44.1kHz. The human hearing range is roughly between 20Hz-20kHz and 44.1 will cover 22kHz just fine.

According to the Nyquist-Shannon sampling theorem, the sampling frequency for converting analog signals to digital, must be greater than twice the bandwidth of the input signal to reconstruct the original perfectly from the sampled version.

To give a visual analogy think about a digital photograph. The sample rate is the number of pixels in the picture. Once you have more pixels than the human eye can differentiate, it does not make a difference to the observer.

When you do post-processing on digital photos however, more pixels are desirable. The same is true in theory for audio, but its much less noticeable. Some audio effects will work internally with a higher sample rate for that reason.

16 or 24Bit?

More important however is the bit depth. To illustrate its role lets take a look at the picture below. Its the same picture, first with 8bit of color per channel (RGB), then with 4bit, then with 2bit and lastly with 1bit per channel. So in the 1bit example, the color of a pixel can only be mixed with either 0% or 100% of red, green, and blue.

The higher the bit depth the more shades of a color are available. With 4bit, red, green and blue each can have 16 different shades which then will be mixed to get a more accurate color per pixel.

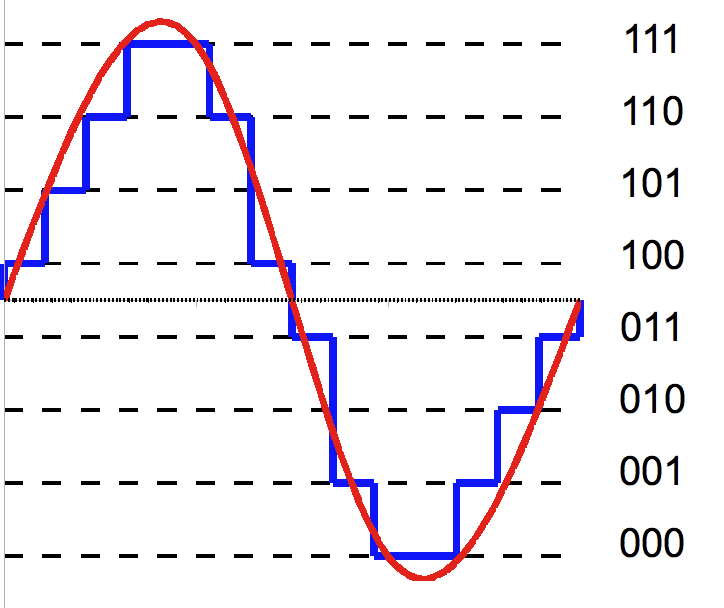

In audio, when a sample of a sine wave is converted to digital, a lower bit depth will provide fewer “shades” or steps to represent the analog signal. The process is called quantization and when analog signals are converted to discrete digital values, quantization noise is introduced as the smooth analog sine wave is now a stepped representation after rounding and truncating the value to fit one of the discrete numbers provided by the bit depth.

(This image is taken from the Wikipedia article about Quantization and is licensed under the BY-SA 3.0 license )

The reason why you want to record in 24bit rather than 16bit is that this quantization noise is much “quieter” than in 16bit. In other words the signal to noise ratio is much better with 24bit which means that it will provide a bigger dynamic range for your recording.

This noise is inaudible in 16Bit as well but once you start processing the digital audio, it can become audible much easier than with 24bit and the dynamic range is “only” 96dB vs. the 144dB for 24bit.

To make it even more obvious lets look at it from a different angle. In 24bit, the quietest signal can be -144dB, in 16bit it’s at -96dB, at 8bit it’s at -48dB which is quite audible.

To hide the quantization noise, it’s beneficial to actually have room to hide it. In 24bit you have all the room in the world, at -96dB 16bit is doing still good enough but at 8bit there is no room to hide the noise as the quietest signal can only be -48dB.

This is the same sound clip first in 16, then in 8bit:

I hope that illustrates the point. If you still want to know more then check out these videos:

- 16 bit vs. 24 bit Audio, What Should You Record At?

- D/A and A/D | Digital Show and Tell

- A Digital Media Primer For Geeks

Do you really need to care?

The simple answer is no. If you record your podcast in 16Bit/44.1kHz it will work, especially if you have a great room, mic and pre-amp. Recording in 24bit however provides some benefits at very little (storage) cost. Especially when you have to do some post processing it can’t hurt to go with 24bits.

If you want to know more details about digital audio I can recommend the book “Mastering Audio” by Bob Katz

TL;DR: My recommendation

Just record at 24bit/48kHz and never worry about it again.

Post-Processing

After the recording, the tracks need to be mixed to be as pleasant, convenient and enjoyable for the listener as possible.

Post-Processing should be applied whenever it can improve the sound but ideally in a way that the listener doesn’t notice. A gate which you can hear muting and unmuting, or which is cutting off the endings of syllables can be quite annoying for the listener.

Lets go through the most common steps of post-processing.

Loudness / Levels

The first step should be to adjust the loudness of all the tracks to a common level. This can be done by playing the tracks back and looking at the level meters and adjust the faders/levels accordingly. Again it would be desirable to keep the target level of all tracks around -12dB on average to leave you some headroom for more processing.

Some people just normalize all the tracks but I don’t like that as it will put the loudest parts right at 0dB, leaving you no headroom afterwards.

Doing it manually should not take more than 2-3 minutes and it does not have to be perfect.

Noise

Once the levels are roughly adjusted, check all the tracks for noise. Especially when there is nobody speaking, check for 50Hz (or 60Hz in the US) hum or any other audible noise.

If you can hear 50 or 60Hz hum, it is quite easy to filter it out with a plugin in your DAW. The same is true for most static noises. I’m using Reaper most of the time and their plugin “ReaFir” is quite powerful at noise reduction.

Here is a 5 minute tutorial on how to use that plugin: Removing Background Noise in REAPER

Gating

A gate is a tool commonly used to reduce noise or crosstalk. When four people sit on the same table, recording a podcast, only one person will talk at the same time, while the others listen. However all microphones will pick up the voice of the speaker, much quieter than the mic of the speaker, but nonetheless, it will be audible.

To remove this crosstalk, you can put a gate on all the tracks. The gate will only let a signal on this track through if it reaches a certain loudness. Ideally only when the person in front of that microphone is speaking. When this microphone is picking up the voices of the other speakers at the table, the signal is much quieter and therefore the gate will close and mute the track.

The same would apply to background noise. Maybe you can hear a washing machine or ac rumble in the background. You could set the gate up so it mutes the track when only the quiet background noise is audible and un-mute the track whenever the signal is louder as in when you are saying something.

The problem I have with gating is, that if your background noise or general noise floor in the signal is quite audible, than it will be very noticeable when the gate opens and closes as the noise disappears and re-appears. Also it must be carefully set up so it does not mute the channel before the end of a word or syllable.

EQ

To some degree an Equalizer can be used for suppressing unwanted frequency ranges. Otherwise it can be used to compensate frequency “coloration” of live microphones or overall tonal balancing. Usually though for podcasts, EQs are not needed that frequently.

De-Essing

A de-esser is a compressor which only deals with sharp “es” sounds. If your microphones are very sensitive to high frequencies, chances are that you will end up with these unpleasant “es” sounds. So the de-esser is focused on these high frequencies and compresses them (makes them quieter) whenever they are occurring, leaving the rest of the signal as is.

Compression

A compressor is the primary tool to control dynamics in loudness. Lets say you did a soundcheck before recording and the person you are recording has a huge dynamic range between the normal conversation and a loud laughter. So you dialed back the gain on the pre-amp to prevent the signal from going over 0dB (clipping) but now the normal conversation level is too quiet.

The compressor would allow you to turn down the loudest parts so you can increase the level for the entire track without clipping and thereby making the quiet parts louder and the louder parts quieter.

The scope of this article is already quite big but to learn how to properly set up a compressor, please check out these videos:

Limiting

A limiter is a more extreme form of compression as it will simply not allow the signal to go over a certain limit. Even as you increase the level of your track, it will try to make it work within the limit by reducing the volume of the loudest parts. There are some other magic tricks involved but it’s amazing how loud you can get a signal with a good limiter, without noticing a degradation of the signal.

The limiter is a great tool for setting the target loudness of your mix and remove any short term peaks that you couldn’t control otherwise.

I’m always using a limiter at the end of mixing either podcasts or music and I’ll set it to -0.6dB so I’m sure the signal is not clipping and there is a bit of headroom for converting the audio to 16bit.

There are different scales and systems to measure loudness. Some are sample based – how loud is the signal at a given point in time, and some are perception based – how loud is a signal perceived by a human over a stretch of time. I’m sure there are more but again this is a subject that deserves an article on its own.

TC Electronic has a very nice overview of the loudness terminology

The important part is that there are loudness standards. They are these days based on the LUFS scale which stands for “Loudness Units Full Scale”. There are different standards on this scale for different applications. For podcasts and music, -14 LUFS seems to be the common standard these days.

Ideally your limiter will allow you to set your scale to -14 LUFS so you have an appropriate reference point when you set it up. Your normal db meters will only show you the momentary loudness, the LUFS meter will give you an integrated / overall loudness indication which relates to the human hearing.

There is another great article explaining LUFS: All You Need Is LUFS

I’m using the excellent FabFilter L2 limiter which also has a LUFS meter built in.

Mono vs Stereo

For me, podcasts do not make much sense in stereo unless you are aiming for a specific immersive atmosphere. Usually though this is more appropriate for audiobooks.

If your intro and outro jingles need to be stereo, you might as well do export the whole episode in stereo even though the conversations mix is mono.

I release all my podcasts in mono and many other people do as well. If you don’t care about the increased file size of stereo audio you can do whatever you feel like. Just remember: smaller files = faster downloads!

Exporting / Encoding

The last step of the process is the export to the final format. Be it mp3, mp4, ogg or opus. In general you need a lower bitrate for speech than for music. An mp3 at 112-128kbit is absolutely sufficient. An mp4 at 96kbit is perfectly fine as well. Ogg and Opus I haven’t used much myself but Opus is doing extremely well at low bitrates for spoken word.

Post-Processing As A Service

If all of that seems too complex to you and you just want to get your podcast recorded and published, there is at least one great service to do most of the post processing for you. It’s called Auphonic and it is absolutely fantastic for eliminating noise, removing crosstalk, adjusting levels, compression, limiting, meeting the target volume standards and exporting. It can be even linked to your podcast publishing platform and auto publish episodes if desired. I’ve been using it for years and couldn’t be happier with it.

But a word of warning is necessary. If your source material is crap, even Auphonic will not salvage it. The better the source material, the easier the job for auphonic (or you) will be and the better the result.

Bonus: Recording a Podcast with Remote Participants

Quite often people will record with guests on the show which are not at the same location. The failsafe option in this scenario is that each party will record their tracks locally and afterwards they get uploaded and mixed by the producer. This will yield the best quality and is safe from quality issues in the voice call.

There is also the option of using StudioLink, which is a free, podcast focussed, OPUS codec based VoIP solution. Due to the OPUS codec the audio quality is so good that often times I can take directly the StudioLink track for mixdown.

Bonus: The Ultimate Podcasting DAW

The german podcasting scene is quite active and one outcome was a mod of the DAW Reaper to become a podcast focussed DAW. It’s called Ultraschall (ultra-sonic) and I can highly recommend checking that out if you’re planning to do a lot of podcasting.

Bonus: Publishing Your Podcast

Lastly if you want to host your podcast yourself, one of the best ways is to do it with a wordpress plugin called Podlove, again a creation of the German podcast community which I have been using myself for the past couple of years as well.

Outro

I hope this was helpful to you. Leave questions, corrections and other ideas in the comment section and share it as you see fit

Freudian slip? 😉 What did you confess in that podcast?

“A mic stand plus a big confessor or dynamic mic also block the vision to some degree.”

Wow that slipped not only through my eyes but also some proof readers 😉

Great post! Instead of a gate I’d recommend an expander if there are problems with loud background noise. It does a similar job like a gate, but it doesn’t completely mute the signal. I think it’s more pleasant to listen to almost not noticeable background noise, instead of a gate kicking in and out. But maybe that’s a question of taste

I do a LIVE broadcast daily and stream LIVE to youtube and mixlr.

In 9 years doing my show I have produced over 6,700 podcasts and I have been using the Plantronics DSP-400 USB headset

which has the following specs below.

Sadly my headset has been discontinued by Plantronics and now I am forced to find a replacement.

At the same time I am looking to improve the quality of my audio and like to know what microphone you might recommend that would have

Stereo, 24 bit, 48kHz-96kHz sampling ability.

Plantronics was one of the few I found that had a DSP built in…..

Digital Signal Processing:

5 channel 16-bit, 48kHz data from USB

24 bit, 100dB signal-to-noise CODEC

32 bit digital audio processing.

Microphone Input:

Mono, 16 bit, 48kHz data

Preset digital EX-6 bands mono

Mic gain stage >50dB range

Up to25dB noise rejection (hypercardiod response)

100Hz-10kHz frequency response

Electret condenser microphone with –38dVB/Pa sensitivity

Thanks for your comment. Unfortunately I’ve never used direct USB headsets as I always went with the dedicated pre-amp / audio interface which offers a bit more flexibility. Therefor I’m afraid I can’t give you a specific recommendation :/